Global Water Challenge Award 2024

1. July 2024Direct impact of microplastics on wildlife

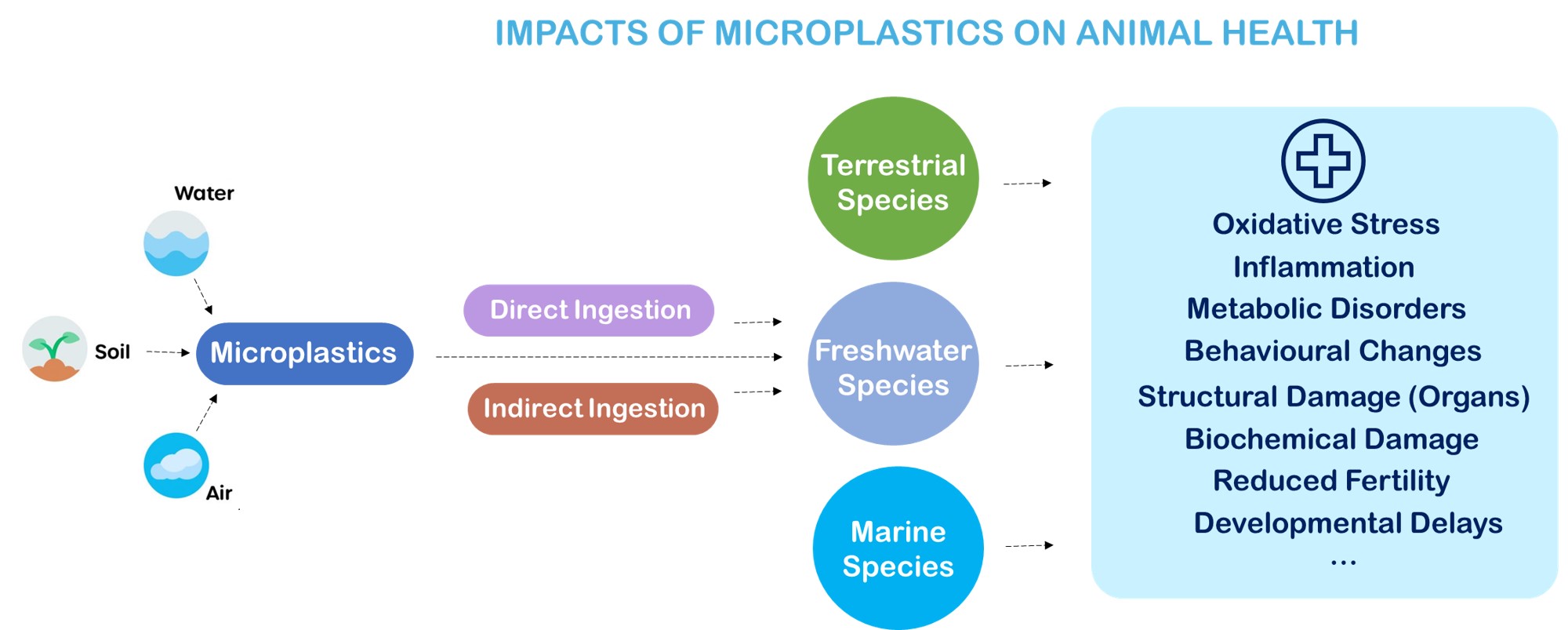

Microplastics have become a ubiquitous pollutant in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. They’ve been detected everywhere from artic ice to deep sea sediments, in fresh (raw) milk, and in the tissues of domesticated animals. Due to their small and varying sizes, they can be consumed at all trophic levels, either directly (ingestion or inhalation) or indirectly (transmitted along the food chain). Microplastics and their associated chemicals may thus accumulate along terrestrial, freshwater, and marine food chains, with long-term negative effects on ecosystems throughout the world.

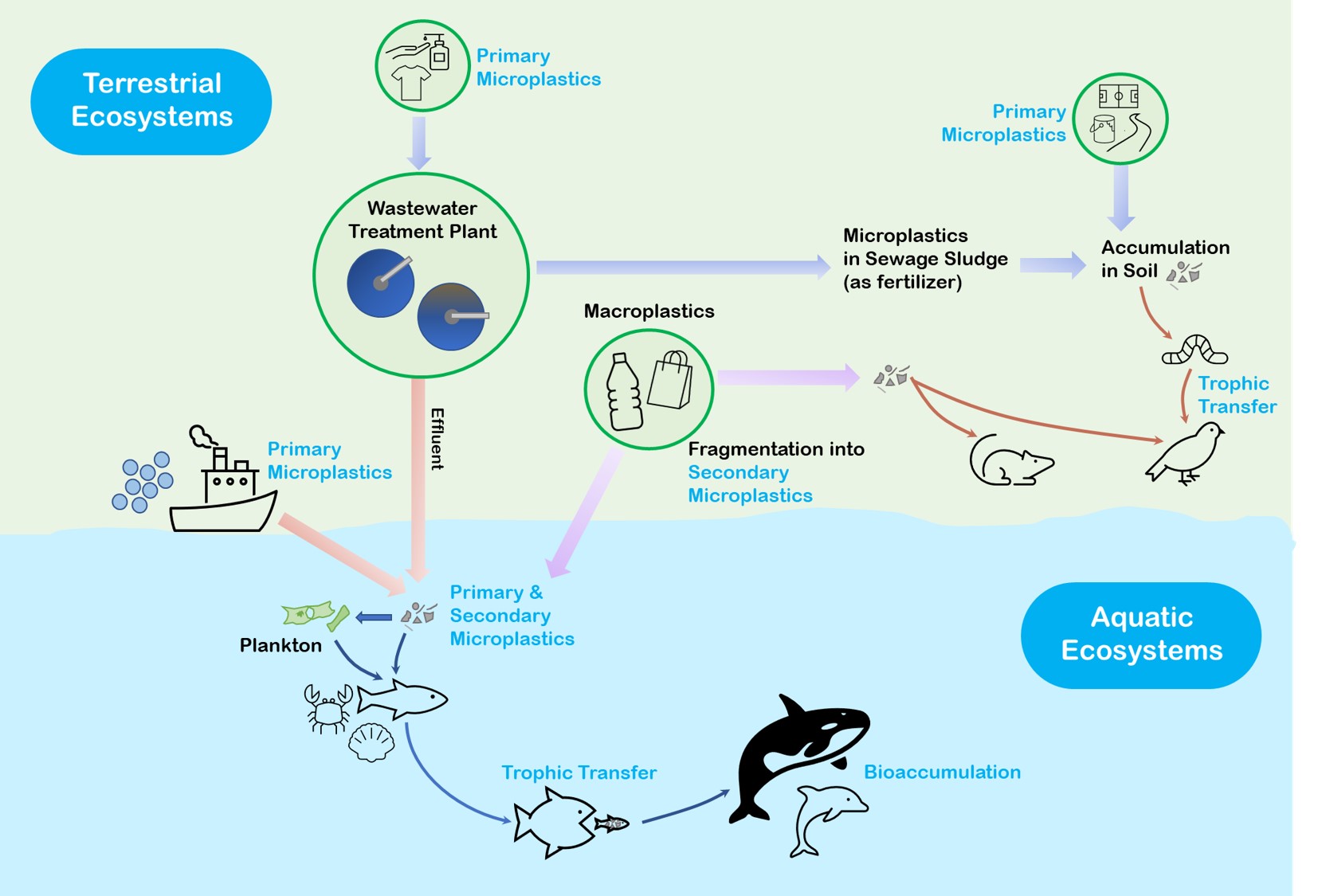

There are numerous indirect and direct sources of microplastics into the environment. Indirect sources include the fragmentation of larger plastics into smaller particles, while direct sources into the environment includes entry via intentional use in cosmetics or paints, release through the washing of synthetic textile or tire abrasion, surface run-off or air dispersal from artificial turf, or release into the environment through wastewater effluents and the use of sewage sludge as a fertilizer.

Rivers transport microplastics to larger freshwater bodies and the ocean and may result in the deposition of plastics along riverbanks and shore banks. Microplastics that are deposited on soils can be remobilized by weather patterns and be transported significant distances by winds, ending up in remote areas. And as microplastics do not degrade, they accumulate in the environment.

Once in the environment, they are ingested by numerous organisms as they are either mistaken for food (due to their size, colour, or biofilms), or taken up accidentally (i.e., through filter-feeding or attachment to food particles). Biomagnification and bioaccumulation then lead to microplastic contamination at higher trophic levels.

Numerous detrimental effects have been observed, with the toxicity influenced by the chemical and physical properties of the polymers and additive properties. The toxicity is likely caused by either:

- ingestion-induced stress

- leakage of chemicals, such as additives

- exposure to adsorbed/released contaminants (i.e., persistent organic pollutants)

The subsequent toxicological effects include impacts on reproduction, population dynamics, oxidative stress, physical blockages, physiology, feeding behaviour and nutritional uptake, as well as metabolic, immune, and hepatic functions. Additionally, chemical additives may leach from the microplastics, that may disrupt the hormone systems of both vertebrates and invertebrates.

But understanding the ecotoxicological impacts of microplastics on organisms, their transfer among food webs, interactions with other environmental stressors, and their impacts across different environmental compartments is a huge challenge and not yet well understood.

It all ends in water: Insight aquatic environments

In marine environments, species at the bottom of the food chain, such as plankton, play a critical role in maintaining the ecosystem balance; they provide food for higher trophic levels and have an important role in carbon cycling. But phytoplankton exposed to microplastics may exhibit various cellular and biochemical effects, including impaired photosynthesis and inhibited growth. Further exacerbating the issue, zooplankton may consume microplastics due to their size relative to natural prey and have been shown to feed less on primary producers due to microplastic consumption. This results in a subsequent decrease in growth and reproduction. Recent models have shown that even at low microplastic concentrations, this may accelerate the loss of dissolved oxygen in oceans.

Further up the food chain, fish may consume microplastics directly, or via trophic transfer. One review which investigated studies 2012-2022 covering 57 countries around the world, found that 926 different seafood species are known to be contaminated by MPs. And recent studies on commercial important fish species, such as Rainbow trout, seabream, and seabass, have also found that up to 63% of fish had MPs in their gastrointestinal (GI) tracts, with 80% of these being fibrous. Fish exposed to microplastics have exhibited numerous toxic effects including reduced food intake, delayed growth, oxidative damage, affected lipid metabolism and cholesterol content in their muscles and liver, structural damage to the intestine, liver, gills, and brain, and negative effects on metabolic balance, behavior, and fertility. A reduction of fertility has even been noted in subsequent generations, leading to further implications on ecosystem functions.

For filter-feeding marine mega-fauna, up to 99% of their microplastic uptake likely occurs through trophic transfer. A study released in November estimates that blue whales ingest up to 10 million microplastics per day, equivalent to almost 45 kilos, compared to the approximately 400,000 microplastics that humpback whales consume daily. For other large marine mammals, a study investigated 5 species and found all specimens sampled (porpoises, dolphins, fin whales, and loggerhead turtles) contained MPs in the stomach and intestines. The potential health impacts of such large consumptions of microplastics on whale and marine mammal health is not well known. However, it’s not just the plastics themselves that are of concern, but the leaching of hazardous chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), bisphenol A (BPA), and phthalates.

And it’s not just aquatic species that are impacted, but also wild coastal animals, such as otters, seals, and various seabirds.

Another concern is the ability of microplastics to carry pathogens that can infect both humans and animals from land-based sources to off-shore areas of oceans. A study released this April investigated three pathogens, Toxoplasma gondii, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Giardia enterica, that are persistent in the marine environment and a cause of illness from shellfish consumption. It was shown that these pathogens can associate with microplastics, particularly microfibres, in sea water and microplastics may thus be a pathway of pathogen transmission into the marine environment, a concern for both wildlife and human health.

What about the terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems?

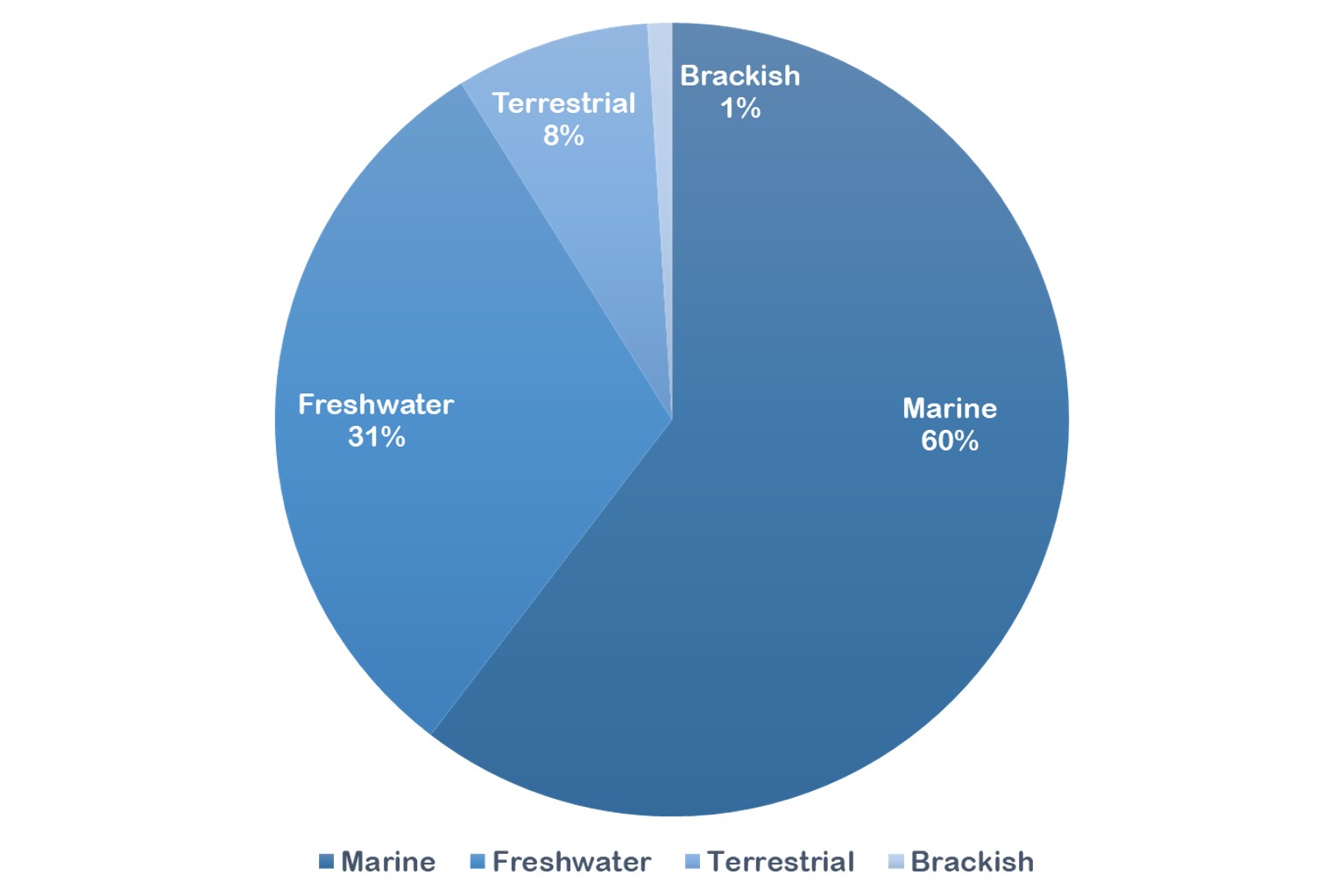

Although much of the research emphasis has been placed on microplastics in marine environments, the impacts of microplastics extend much farther than the oceans.

Approximately 80% of microplastics found in marine and coastal environments are produced, used, and disposed of on land. And although far less attention is paid to the sources and environmental fates and implications of terrestrial microplastics, researchers estimate that terrestrial microplastic pollution may be 4-23 times higher than in marine environments.

Soils have thus been suggested to be a larger reservoir for plastics in the environment than the oceans, with numerous long-term negative effects.

Soils are full of microscopic life; they are the foundation of the terrestrial food chain and are important for supporting biodiversity. There is growing evidence that microplastics have an impact on terrestrial organisms that facilitate critical ecosystem functions.

For example, mites, nematodes, and earthworms all play an essential role in decomposition and releasing nutrients into soils. But studies have shown that microplastics in the soil result in weight-loss and a change of earthworm’s burrowing habits, and a decline in mite and nematode numbers. Further, recent insights have revealed that the toxicity on earthworms is time-dependent, indicating that even biodegradable plastics may trigger toxic effects, such as oxidative stress and intestinal tissue fibrosis. Thus, it is critical to understand these interactions to prevent the degradation of soil quality and any subsequent reduction in plant and organism survival.

An increasing number of studies have also started to investigate the impacts of microplastics on terrestrial mammals, primarily mice and rats, as well as small terrestrial birds. It has been demonstrated that in mice and rats, nano plastics can translocate within the body to various organs and tissues, with particles being detected in the kidneys, liver, lungs, spleen, hearts, ovaries, testes, and intestines. This resulted in biochemical and structural damage with noticeable dysfunctions of the intestine, liver, and excretory and reproductive systems. Microplastics have been found in the lungs of wild birds, as well as in their GI tracts. A study conducted on the carcasses of 16 raptors from the Central Californian coast found MPs in all birds, with an average of 12 MPs/bird, with fibres being the predominant particle type, while another study found MPs in 63 individual birds of 8 predatory bird species in central Florida. The implications of MPs on bird health is not yet known, but one study has found an observable reduction in body mass after only 9 days of ingestion of 11 and 22 microplastic particles/day/bird.

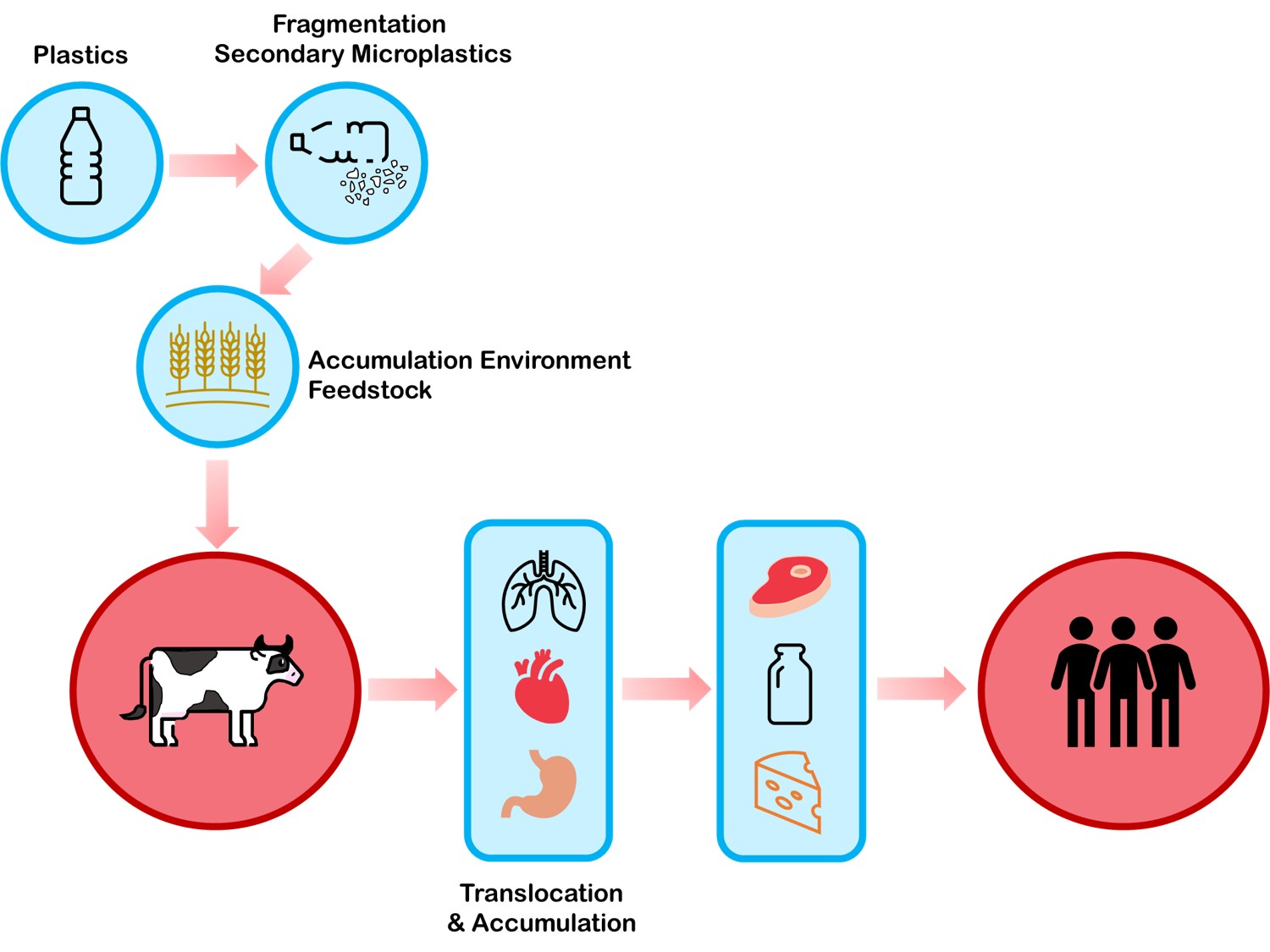

The contamination of the human food chain is not just due to microplastics found in seafood. Almost 80 percent of meat and dairy products from farm animals contain microplastics, as revealed in a recent study, with 7 out of 8 beef samples, 18 out of 25 tested milk samples, and all blood samples, containing plastic particles. It is assumed that a large amount of the plastic originates from their feed – all samples of feed pellets and shredded feed had plastics, while no contamination was found in fresh food. However, the toxicological risks of these findings on human and animal health are not yet known.

Technology alone is not the solution

Microplastics are prevalent and persistent in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. The detrimental impacts on various ecosystems and species are complex and varied, but there is increasing evidence of bioaccumulation and biomagnification of microplastics and their chemical additives along food chains and numerous deleterious effects at all trophic levels. They have been shown to interfere with nutrient productivity, cause physiological stress in organisms, and ultimately harm biodiversity and ecosystem stability.

The degree of these impacts depends on the particle composition, size, dose, and exposure parameters. Thus, it is critical to first determine the entry pathways, as well as the exposure routes and amounts to identify the risks and mitigate the impacts in various environmental compartments. This requires standardized detection methods to ensure that comparable, reliable, and transparent data on microplastic concentrations can be obtained.

Once in the environment, microplastics are impossible to remove. And as the amount of plastic entering the environment continues to increase, it becomes ever more critical to develop solutions to target microplastic removal at the source and prevent unintentional release into the environment.