Partners in Mission: Nordic Water

27. December 2022

Unlock Potentials for Water without Microplastics

1. February 2023The EU’s Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive – an overview

Untreated urban wastewater is a main source of water pollution; it must be efficiently treated to prevent the release of bacteria, viruses, nitrogen, phosphorous, along with other pollutants. Therefore, modern wastewater treatment plants are equipped with more and more cleaning stages to respond to current and future issues. The control body for monitoring and pollution prevention is the EU Urban Wastewater Directive (Council Directive 91/271/EEC).

Since 1991, the Directive has been in place to protect the environment and human health from the detrimental impacts of untreated wastewater through the proper collection, treatment, and discharge of wastewater by towns, cities, and settlements. Although this has resulted in improved water quality across Europe, with an overall compliance of 90%, a large amount of pollution is still not restricted or regulated, such as micropollutants and microplastics. Thus, the EU has released a proposal for a revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive at the end of 2022.

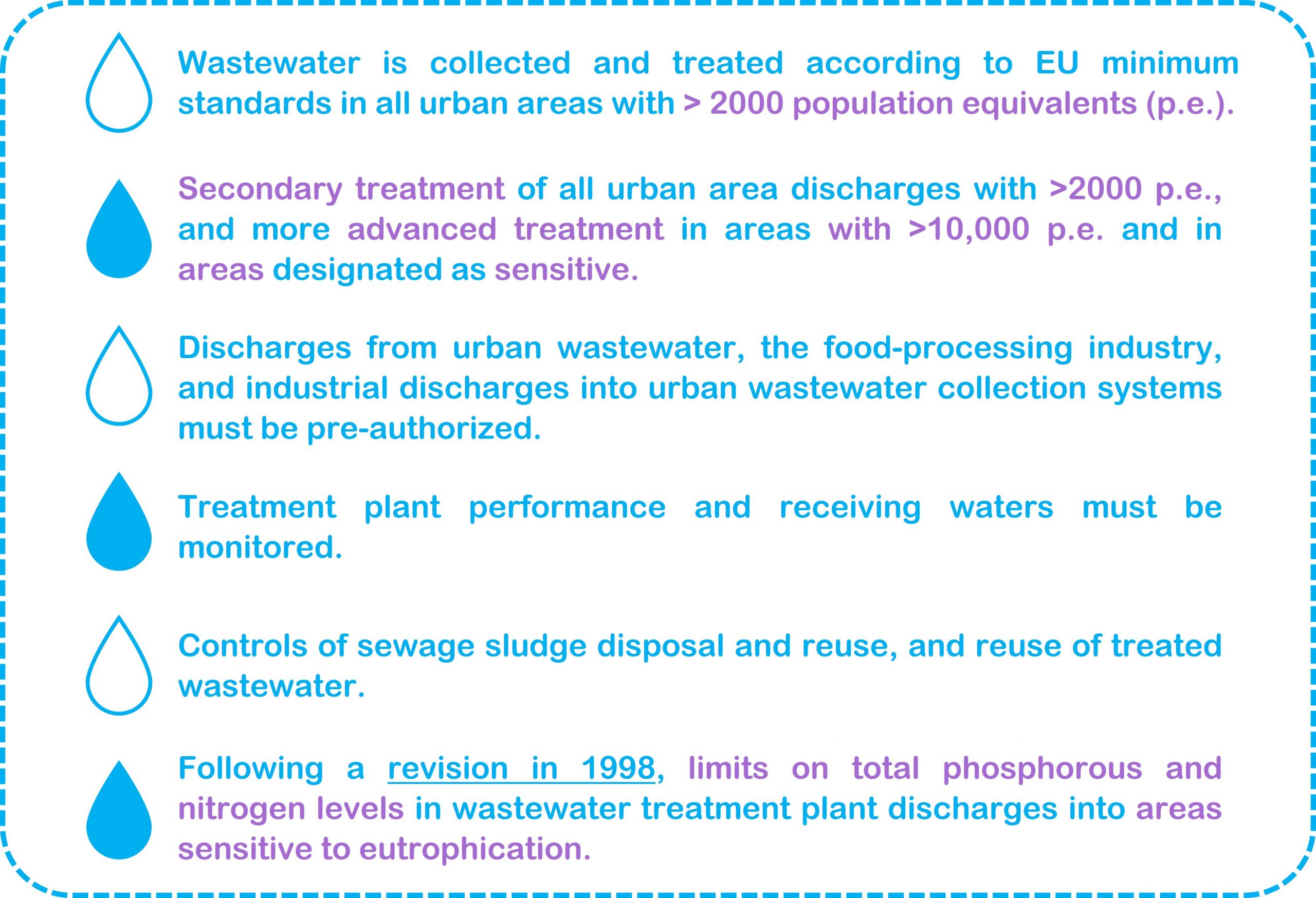

Our blog provides an overview of the proposed changes and their potential impact, as well as the challenges involved in making a measurable impact. The major goal is to pursue synergies with other EU legislation and to meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive, the Bathing Water Directive and the Drinking Water Directive. And these are the current requirements of the EU directive on urban waste water:

Assessing the effectiveness of the directive

The 2019 REFIT Evaluation of the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive determined that although water quality has improved through the reduction of organic matter and other pollution, with 92% of European wastewater adequality treated, there is still a large amount of pollution not covered by the current regulations, such as the pollution from smaller cities, storm water overflows, and residues from the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (responsible for 92% of toxic pollutants). Large amounts of micropollutants are released into EU water bodies every year from urban wastewater treatment plants, a major concern for the environment and public health. Further, wastewater treatment is one of the main consumers of energy in the public sector.

The REFIT Evaluation resulted in the release of a revised Directive on Oct. 26, 2022, with an emphasis on a circular economy approach, achieving energy neutrality, extender producer responsibility for micropollutant removal, and the monitoring of microplastics and health parameters. The revision, together with the revised list of groundwater and surface water pollutants (with thresholds for a variety of chemical levels stated within the surface water pollution directive) , is considered a vital step towards achieving the European Green Deal's zero pollution ambition.

What are the main implications of the revised Directive?

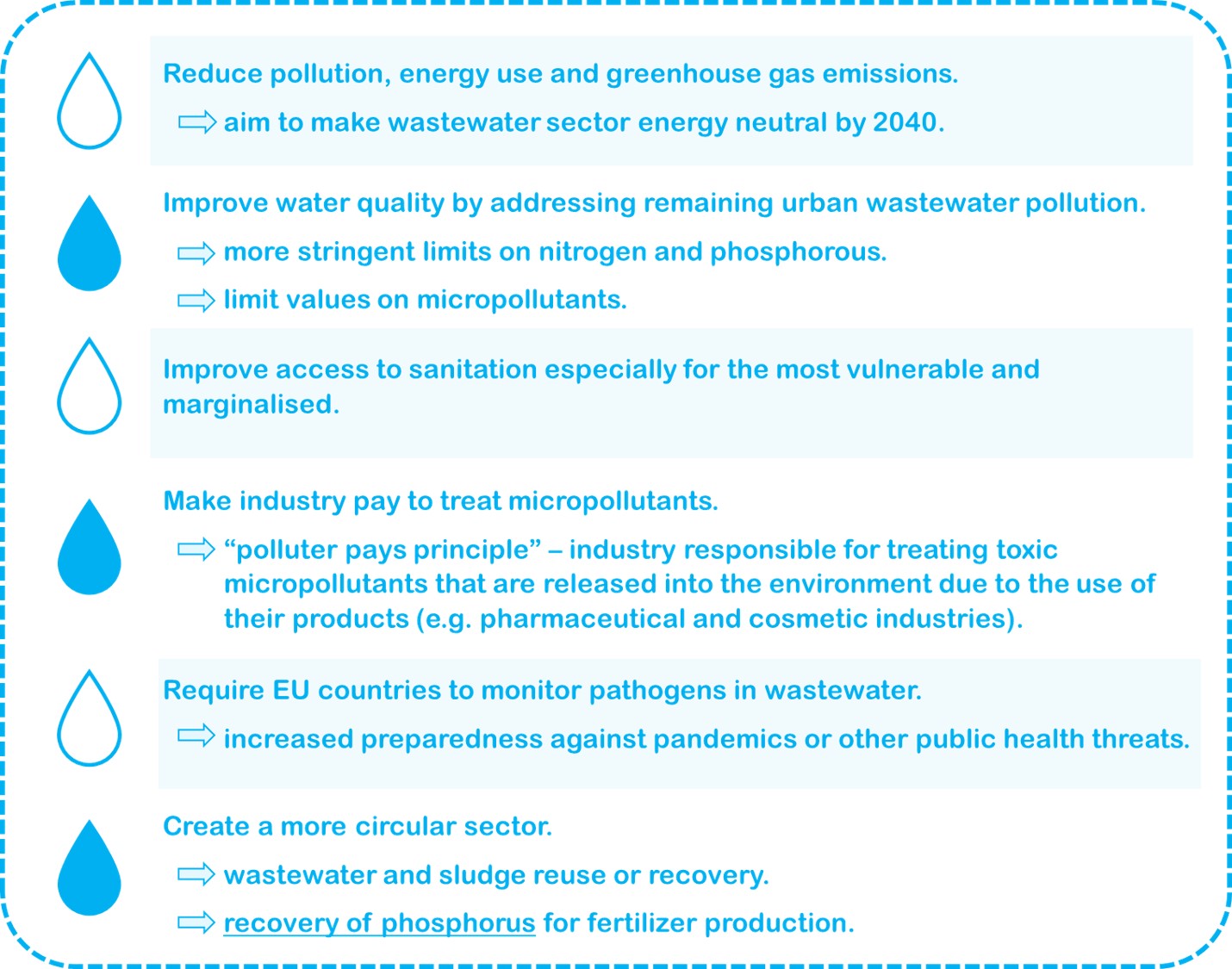

The revised Direction aims to progressively apply several measures that will:

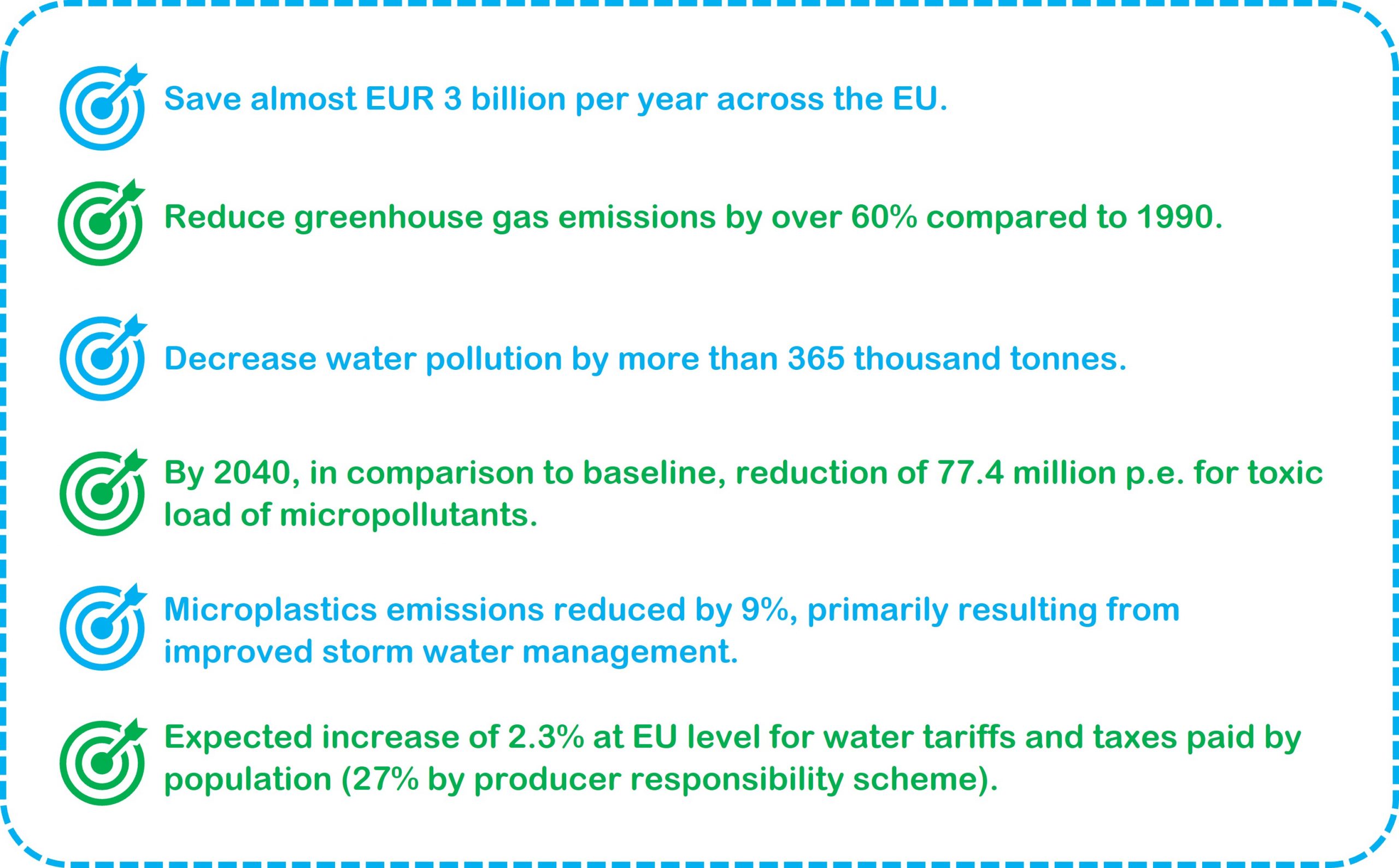

The European Commission claims that by 2040 the new rules will:

What are some of the relevant updates that will be in place to achieve these targets?

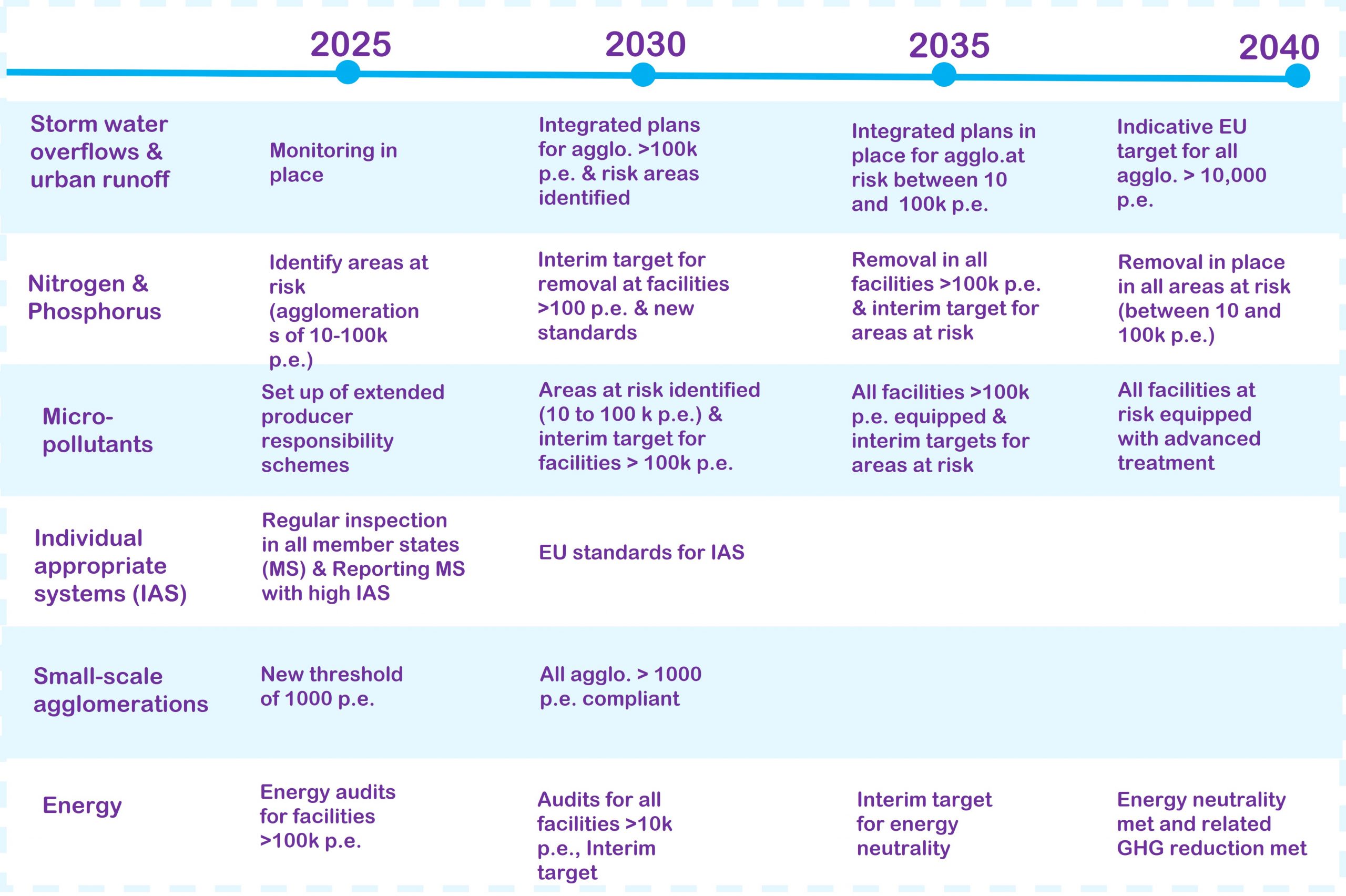

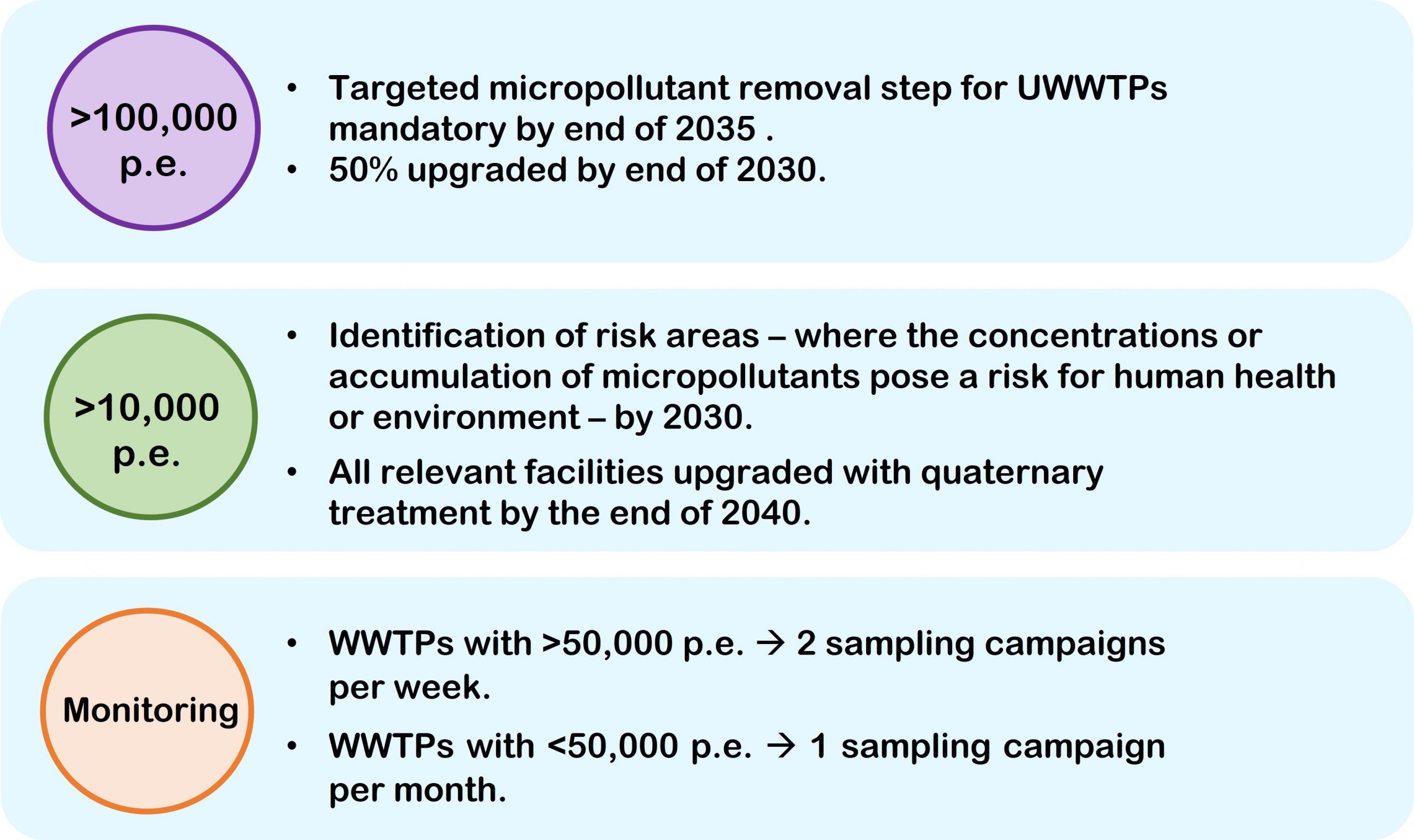

The scope of the previous directive will be enlarged to cover all cities with >1000 population equivalents (p.e). Larger facilities (>100,000 p.e.) are obligated to establish a locally integrated urban wastewater management plan to combat pollution from rain waters (urban runoff and storm water overflow) by 2030 and mid-size facilities (>10,000 p.e.) where rain waters pose a risk to the environment or human health will be required to have a plan in place by 2035.

Tertiary treatment for the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus is now mandatory for all larger and will be necessary for discharges from agglomerations with a p.e. between 10,000 and 100,000 p.e. in areas sensitive to eutrophication.

All facilities serving >10,000 p.e. will further be required to achieve energy neutrality by the end of 2040. Mid-size and larger wastewater treatment plants must therefore ensure that the total amount of renewable energy produced nationally is equivalent to the amount of energy used by such wastewater treatment plants. Energy audits of urban wastewater treatment plants will be carried out at regular intervals, with a focus on the identification and utilization of biogas production and reduction of methane emissions.

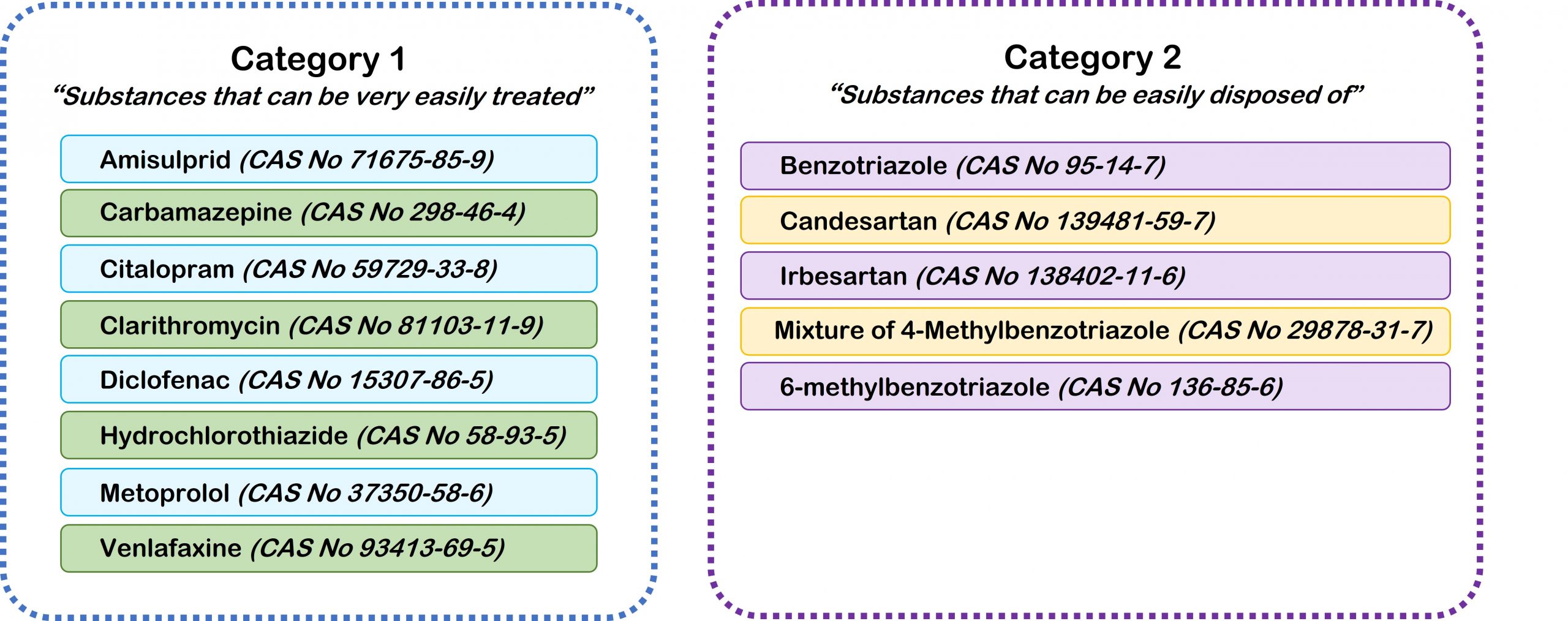

What are the proposed restrictions on micropollutant levels?

A total of 13 micropollutants have been identified in the revised Directive, stated as “substances that can pollute water even at low concentrations”. Limit values for these micropollutant levels will be established and a removal percentage of 80% must be achieved for at least 6 of the substances. The average of the percentages of removal of all substances used in the calculation will be used to determine whether 80% removal has been achieved.

The costs of advanced wastewater treatment will be considered under a system of extended producer responsibility, whereby industries that are producing the polluting compounds must also contribute to the cost of their removal from the wastewater via quaternary treatment, as well as to their monitoring. The pharmaceutical and personal care product industries are two of the main sources of micropollutants; the additional treatment costs should therefore also incentivise placing less harmful products on the EU market.

What about microplastics?

The Commission has identified microplastics as a source of concern but stated that treatment facilities are able to capture them relatively well; it does not point out that WWTPs remain a major source of microplastic entry into the environment due to the large volumes of wastewater effluents. Therefore, no restrictions on microplastic levels have been implemented.

However, it is claimed that improved storm water management will reduce emissions by 9%, and regular monitoring of the presence of microplastics will be required at the inlet and outlet of urban WWTPs with >10,000 p.e.

Facilities for >100,000 p.e., must sample at least twice per year with a maximum of 6 months between samples while facilities for >10,000 p.e. are required to sample only once every 2 years. WTTP (>100,000 p.e.) must also monitor the presence of microplastics in sludge. A methodology for the associated monitoring and detection is to be established.

But how is implementation ensured? Does such a legislation really ensure compliance?

When looking at EU member states, there are many countries that still do not comply with the current EU UWWTD. For example, In Croatia, only 7% of their sewage is treated in line with the legislation, while Romania, Bulgaria, and Ireland have only 14%, 30% and 44% adequately treated, respectively. So how does the EU ensure that countries are upgrading their sewage treatment systems in line with the directive; are there any legal implications if the countries do not follow suit?

According to the EU treaties, the Commission can take legal action against countries that fail to implement EU law through an infringement procedure. Possible infringements of EU law are identified based on investigations carried out by the Commission, or due to complaints from citizens, businesses, or other stakeholders, and the issue may be referred to the Court of Justice, who can then impose financial sanctions.

But the actual amount and impact of infringement procedures appears to be minimal, taking many years to fully implement. For example, no infringement procedures have been initiated against Croatia or Bulgaria for their lack of compliance regarding urban wastewater treatment. And although letters of formal notice were issued to Romania in 2018 and 2020, by 2022 the issue was still not resolved and a reasoned opinion issued. The Commission stated that the case may be referred to the Court of Justice of the European Union if Romania did not reply within 2 months, but no action has yet been taken. And while Ireland was first issued a formal notice in 2013 and taken to the Court of Justice in 2018, the implementation rate remains low.

As many regions and agglomerations fail to adhere to the regulations outlined in the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, and little action is taken to ensure compliance, it is unlikely that relevant urban wastewater treatment plants among all member states will sufficiently install quaternary treatment options within the given timeframe.

Challenges regarding the proposed revision

With growing evidence on the detrimental impacts that micropollutants and microplastics have on the environment and human health, the scientific community, policy makers, and public all recognize these contaminants as an increasingly important issue. However, water quality is unfortunately often not a driving factor in politics and the implementation of effective regulations preventing microplastic and micropollutant entry into the environment is slow or lacking.

Requiring WWTPs to upgrade their facilities for the removal of micropollutants and developing standardized monitoring methods is a step in the right direction – if countries comply with the new measures. But the new directive downplays the important role WWTPs play in microplastic release into the environment and requires only minimal and ineffective monitoring of microplastic concentrations, despite the existing knowledge of WWTP as a main direct source of microplastics into the environment. Thus, the directive does not facilitate targeted microplastic removal in quaternary treatment upgrades at wastewater treatment plants. This will make the process slower and more expensive than if treatment plants are upgraded to target both micropollutants and microplastics at one time.

Further, many EU countries still do not comply to the measures laid out in the original urban wastewater treatment directive and little initiative is taken by the EU to ensure that countries adhere to the laws; thus, the process to upgrade facilities with quaternary treatment will likely be slow, with an initially low overall measurable impact.

Although it’s positive that industries will be forced to contribute to the costs of micropollutant removal, there should be greater emphasis on preventing their production at the source, and to ensure that the use of alternative toxic substances that are not removed or monitored within wastewater effluents does not increase.

What is our strategy to move faster towards microplastic-free processes?

At Wasser 3.0, we take a data-driven approach to drive sustainable and efficient action towards microplastic-free waters. This includes sustainable removal solutions, as well as data on the amount of microplastics in wastewater effluents – providing a basis on the importance of both their removal from wastewater effluents, but also the prevention of microplastics further up the value chain. Since 2021 we are running a long-term monitoring of micropollutants and microplastics at our home-base in Landau.

Effective sustainable process design begins with implementation at the source. For industries, this means adopting a circular approach, which can further minimize the costs that are associated with the polluter-pays-principle – innovative and cost-effective solutions mean it costs less to act. By reducing the water consumption and transforming waste into a resource, industries can act for a larger positive environmental impact while still having an economic benefit.

Overall, prevention is key. Targeting microplastics at the source is a much more effective and controllable approach to prevent downstream microplastic emissions and thus their entry into the environment than removing them from municipal wastewater treatment plants or attempting to remove them once they are in the environment. The earlier the pollution is avoided, the better it is for the environment, wildlife, and human health.