Open House for water without microplastics

11. August 2022

The challenge of microplastic regulation

28. October 2022Plastic and microplastics in the environment - current status of regulations and laws

Plastic production continues to increase and microplastics have been detected nearly everywhere on earth – from arctic snow to human blood – yet there is still no single comprehensive law that regulates microplastic input into the environment.

The development of regulations is a slow and ongoing process; this article provides information on the current laws surrounding plastics and microplastics, alongside the associated challenges and chances.

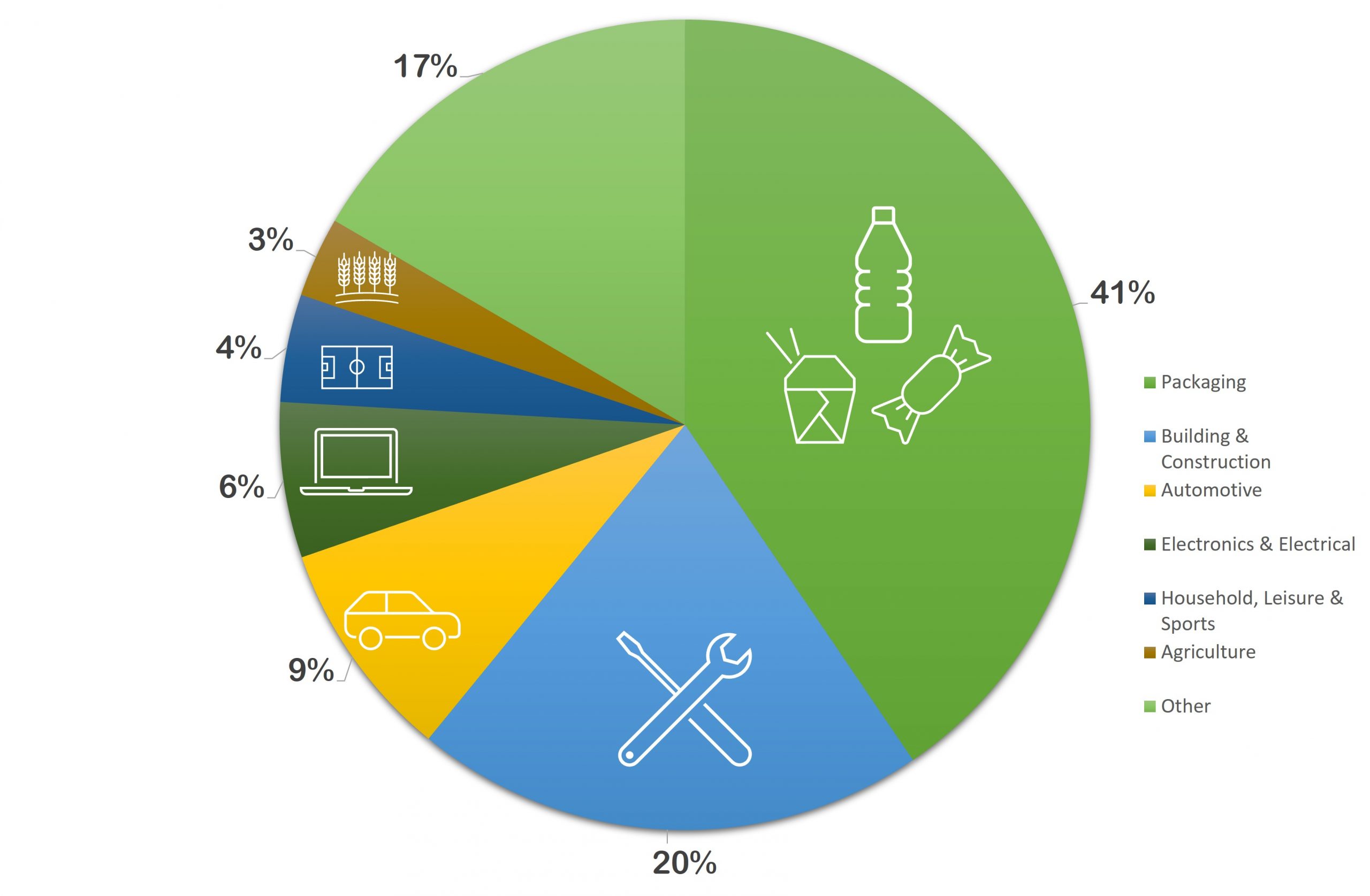

The demand for plastics is increasing alongside the associated environmental impacts. Since the 1960s, plastic production has increased 20-fold.

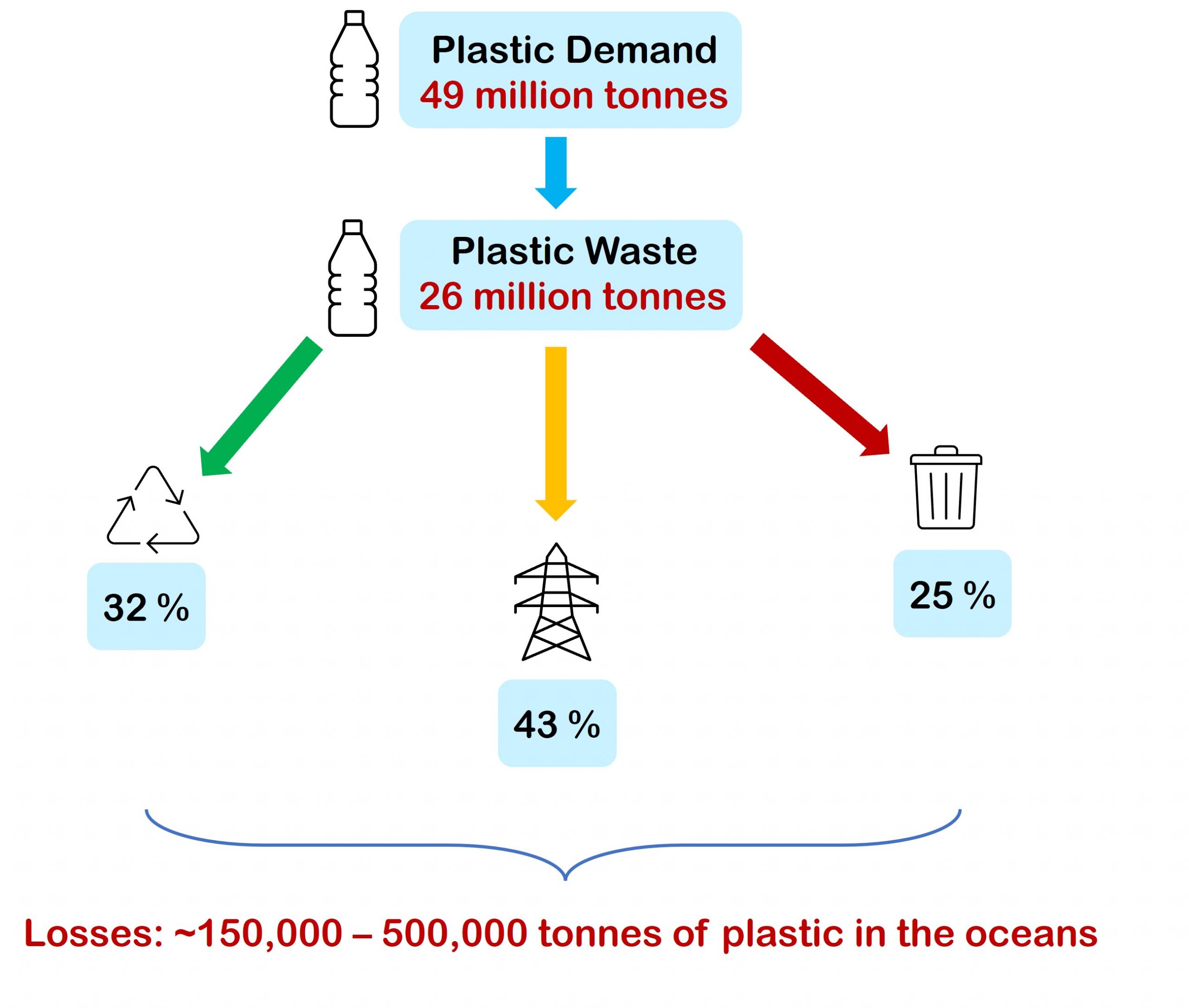

In the EU alone, the yearly plastic demand is approximately 49 million tonnes, resulting in roughly 26 million tonnes of plastic waste. Of this, only 32% is collected for recycling, while 25% is sent to landfills and approximately 43% is used for energy production via incineration.

Yet the demand for recycled plastics is only 6% of the total plastic demand in the EU, with the recycling sector suffering from low commodity prices and uncertain markets. An estimated 150,000 to 500,000 tonnes of plastic ending up in the oceans annually from the EU alone.

EU sources of plastic pollution have been found to end up in vulnerable marine areas such as the Arctic Ocean, with detrimental impacts on these sensitive ecosystems.

EU, Green Deal & co... Where are we in 2022?

To tackle the increasing challenges of plastic waste, the EU developed the Plastics Strategy in 2018 as part of the Circular Economy Plan of the EU Green Deal.

The Plastics Strategy is comprised of various directives and policies that aim to protect environmental and human health and contribute to the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals by transforming the way that plastic products are produced, designed, used, and recycled within the EU, while also initiating change at a global level.

Through this, less plastics and microplastics should ultimately end up in our oceans and the environment.

Small steps in the right direction - the EU single-use plastic directive

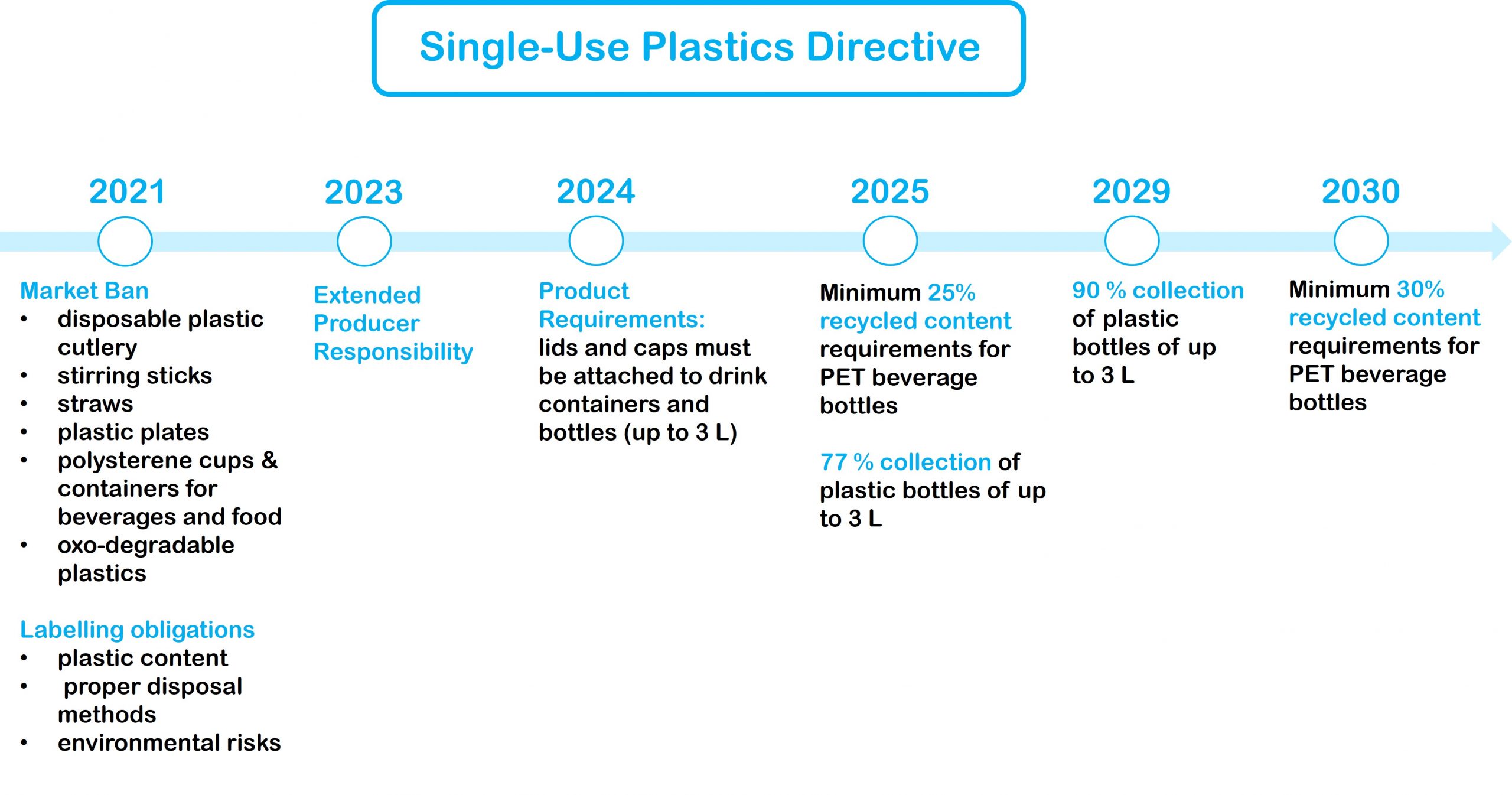

The EU Single Use Plastics and Fishing Gear Directive was signed in 2019, which forbid the use of numerous single-use plastics, such as disposable plastic cutlery, plastic straws, polystyrene food containers, and banned products composed of oxo-degradable plastic (conventional polymers containing additives that increase the material’s oxidation and fragmentation when exposed to UV light, and/or heat and oxygen) as of July 3, 2021.

It further dictates that from 2025 PET bottles must be made of 25% recycled material, and by 2030 this should increase to 30%. The Packaging Act (developed in 2019) stipulates that 63% of plastic packaging must be recycled by 2023.

France implemented additional restrictions, such as a ban on plastic packaging for fruits and vegetables which began in January 2022, with an aim to extend this to all produce by June 2026. Similarly, Spain is drafting a decree that will prohibit the use of plastic packaging for produce under 1.5 kg beginning in 2023.

Global perspective: many stakeholders - many opinions

However, plastic is not just a European issue, but a global one. Researchers have estimated that in 2019, 850 million tonnes of CO2 were emitted due to the production and incineration of plastics. And a large portion of plastic waste in the EU is exported to third countries, where the environmental regulations are less stringent; thus, instead of solving the plastic problem, it simply shifts it. Plastic is “part of a globally connected value chain”, the current national and international legislation and management approaches are typically fragmented, insufficient, and often focus on plastic disposal, rather than a coordinated transboundary approach that addresses plastic across its entire lifecycle – from resource extraction through consumption, distribution, to disposal. For example, legislation exists on single-use and marine plastics, and the export of certain plastic waste, yet there is no legislation that takes a holistic approach. This requires improvements in plastic recycling and waste export, the continued reduction in plastic packaging and single use plastic waste, and an enhanced a circular economy approach.

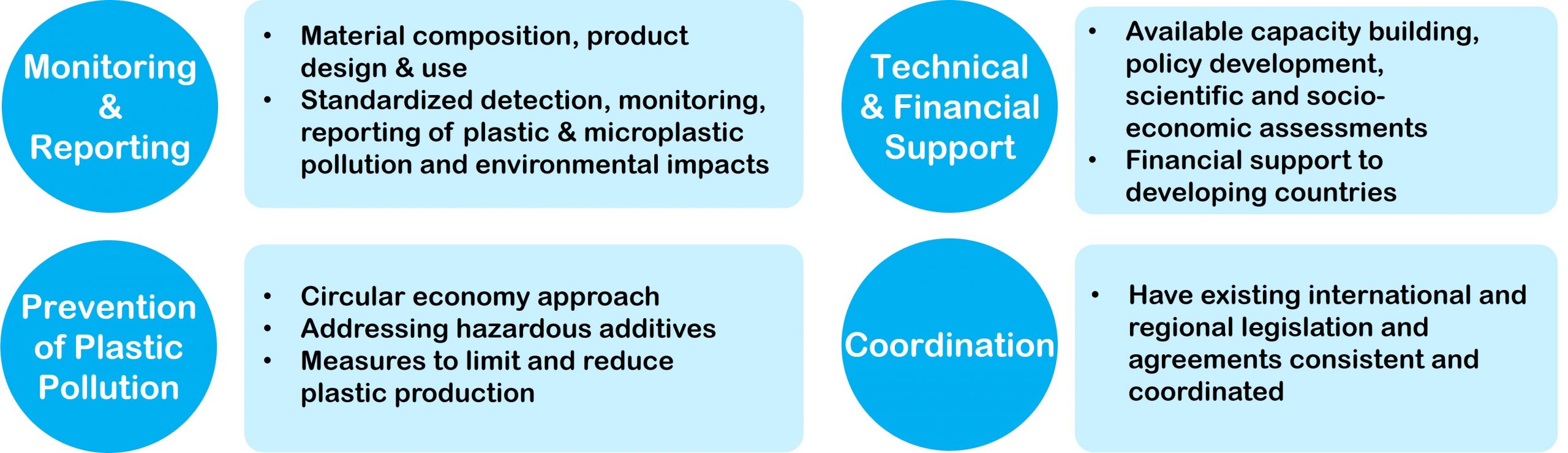

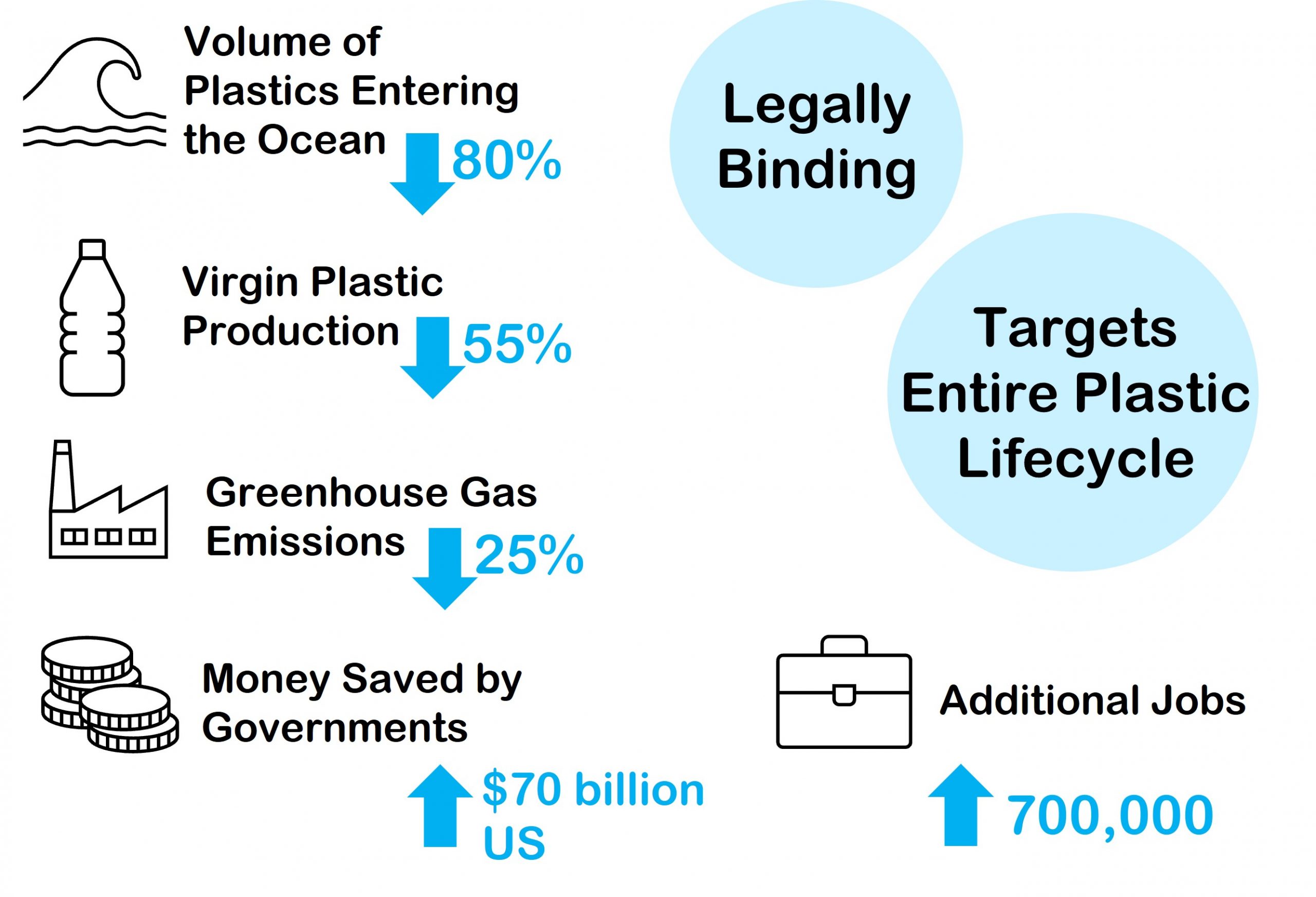

The need to agree on measures against plastic pollution at a global level in a holistic and coordinated way, especially towards achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, is clear and progress has been made with the signing of the “End Plastic Pollution” agreement by 175 countries at the United Nations Environmental Assembly’s 5th session (UNEA-5.2) in March 2022. Four key categories that require action to fill legislative gaps were identified.

"Act on. Now!"

An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established that will develop a legally binding instrument tackling plastic pollution by the end of 2024. As part of this initiative, the “High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution” was launched in August 2022.

The coalition includes Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Iceland, Peru, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Senegal, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, and has the goal of ending plastic pollution by 2040. The Coalition will meet to identify priorities for the negotiating sessions of the INC, develop strategic goals for reducing plastic pollution, and will arrange events for awareness.

There is still room for improvement....

Further global initiatives include the Basel Convention, the UN’s Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, and the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues.

The Basel Convention is currently the only legally binding global regulation that addresses transboundary movements of plastic waste. In 2018, a proposal was submitted by Norway to specifically include plastic waste in the Annexes of the Basel Convention. This aimed to increase the control of transboundary movements of plastic waste, thereby restricting the flow of plastic waste into countries that do not have sufficient means for environmentally sound plastic management. The amended annexes were included in the Plastic Waste Amendments, which were adopted in 2019 and entered into force in January 2021. In 2018, China introduced import restrictions on plastic waste. This resulted in increased shipments to alternative countries in which plastic waste is often mismanaged, primarily Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Turkey. But with the tighter regulations introduced in 2021, there was a 25% reduction in the amount of plastic waste exported from Germany compared to 2020. Although such decreases in plastic waste export may initially result in higher landfilling rates, it should ultimately instigate a push towards taking a more circular economy approach. Until now, only “hazardous” plastic wastes are subject to the limitations outlined in the Plastic Waste Amendments. The procedures for non-hazardous plastic wastes will be reviewed in 2024.

While reducing the total plastic production and adopting a circular economy approach should subsequently correspond to lower levels of secondary microplastics (microplastics formed in the environment from the fragmentation of larger plastic materials), there is still a significant amount of microplastic pollution from sources such as cosmetics, textiles, tire particles, and paints, that must be addressed.

To date, there is no single comprehensive law that regulates microplastic entry into the environment, although numerous EU directives partially address the issue and the latest draft of the REACH Annex XVII, which would restrict the intentional use of microplastics in products, has been released this year. The upcoming blog post will discuss the restrictions proposed in the Annex XVII, additional directives addressing the issue, as well as progress on microplastic restrictions in other countries.