(Micro-)plastics: Status of regulation and laws

17. October 2022

Microplastics and human health

10. November 2022Global challenge of microplastics: Where do we stand on regulations and legislation?

Progress has been made in many countries, including the UK, Canada, and the United States, to restrict the use of microbeads, yet there is still no single comprehensive European law that restricts the intentional use of microplastics in products or regulates unintentional releases through their concentrations in wastewater effluents and their subsequent input into the environment. But effective microplastic legislations are critical for reducing environmental levels.

The United States and Canada are focusing mostly on monitoring programs and regulations that will improve the understanding of the microplastics issue. California released a policy handbook in August 2022, defining standard testing and reporting methods of microplastics in drinking water and will require up to 30 of the states drinking water providers to begin quarterly testing for two years, starting in the fall of 2023. The EU’s focus, however, is primarily on the intentional use of microplastics in products. Let´s have a closer look at current developments.

For years, only estimations have been made regarding the volume of microplastic input into the environment

Microplastics are synthetic polymers < 5 mm often containing functional additives. They are divided into two main categories: 1. Primary microplastics (directly released into the environment) and 2. Secondary microplastics (formed from the degradation of larger plastic particles).

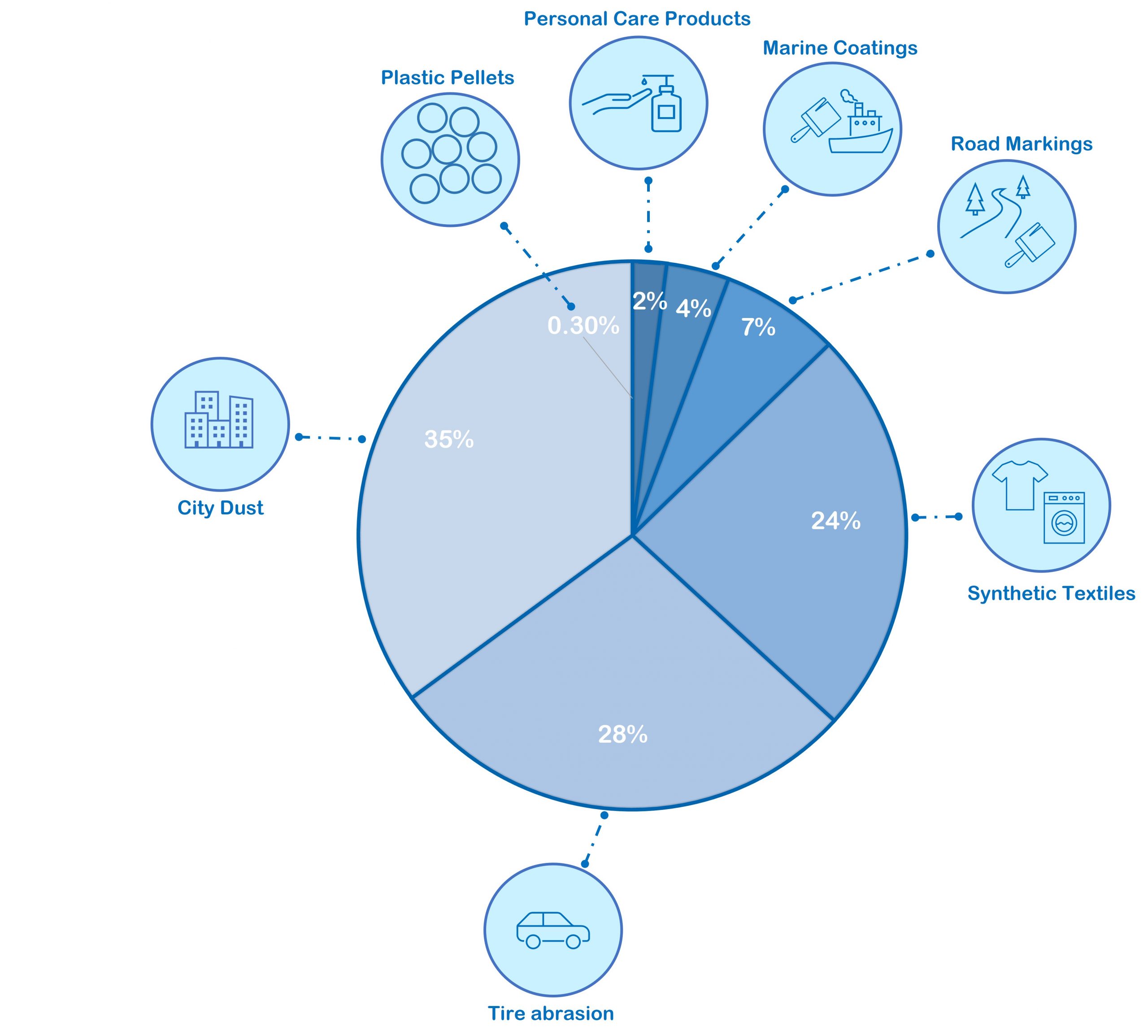

At a global scale, the main primary sources have been identified as tires, synthetic textiles, marine coatings, road markings, personal care products, plastic pellets, and city dust. Of these, only personal care products are classified as an intentional microplastic loss. In higher income countries, with adequate disposal methods and waste treatment facilities, primary microplastics are the main source of plastic into oceans, with 98% stemming from land-based activities.

Each year in the EU, it is estimated that approximately 150,000 tonnes of microplastics are deliberately used (i.e. in personal care products, detergents, fertilizers, and paints) with 42,000 tonnes entering the environment.

When is the right time to start actions on microplastics?

Although microplastics are still not officially classified as hazardous substances or micropollutants, there is increasing evidence of their detrimental environmental and health impacts. And once in the environment, they are almost impossible to remove. There is thus increasingly high pressure from the public and scientific community to implement microplastic restrictions. But action is possible directly and immediately. Even without laws.

It stalls at the political level

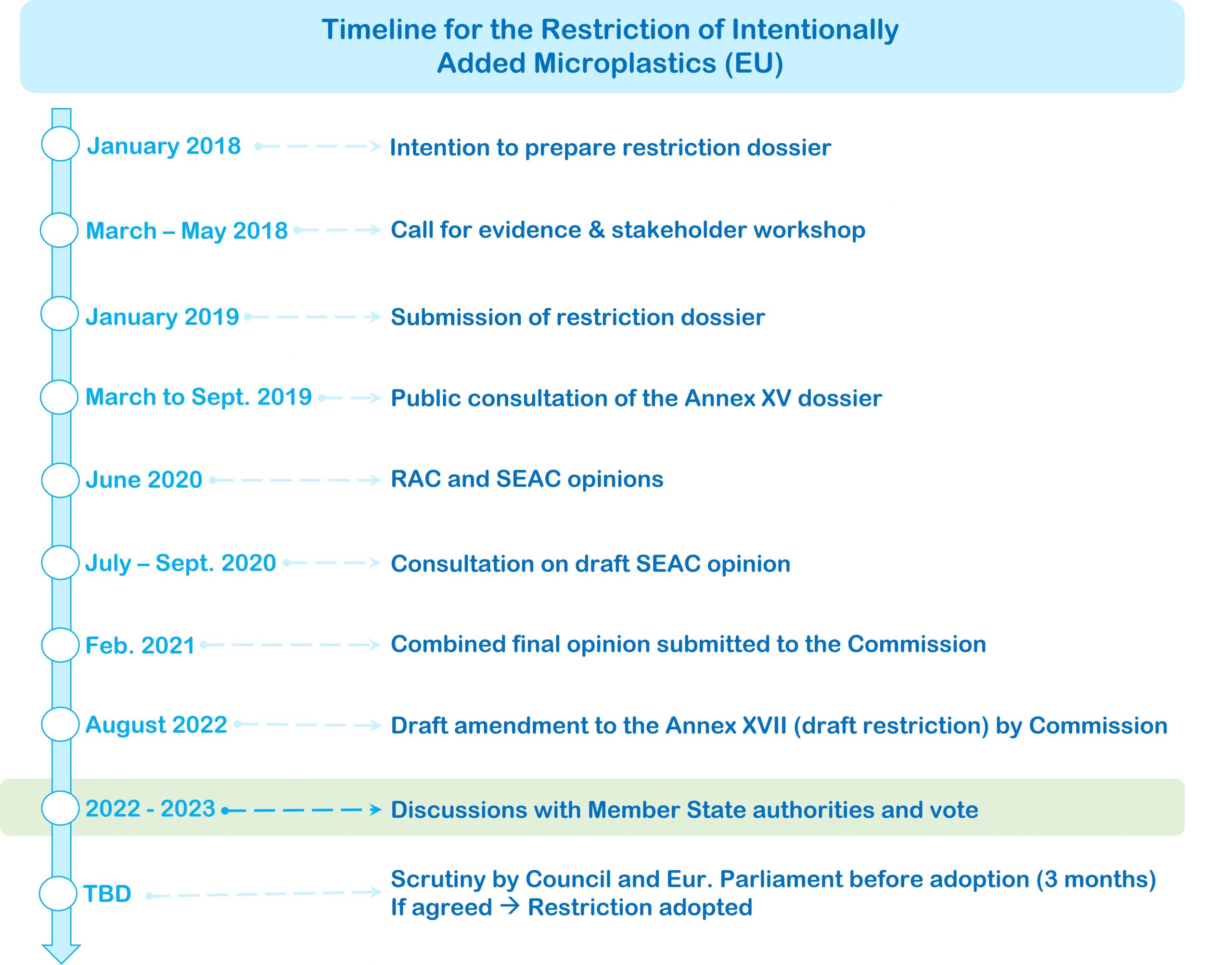

In order to determine appropriate measures, the European Commission requested in 2018 that the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) assess available scientific data and develop a proposal for the restriction of intentionally added microplastics under the Regulation on the Registration, Evaluation, and authorisation of Chemicals (REACH). Through ECHA’s in-depth investigation on the risks and hazards posed by microplastics, they determined that microplastic should be considered as a non-threshold substance for risk assessments.

In other words, any release into the environment is considered a risk.

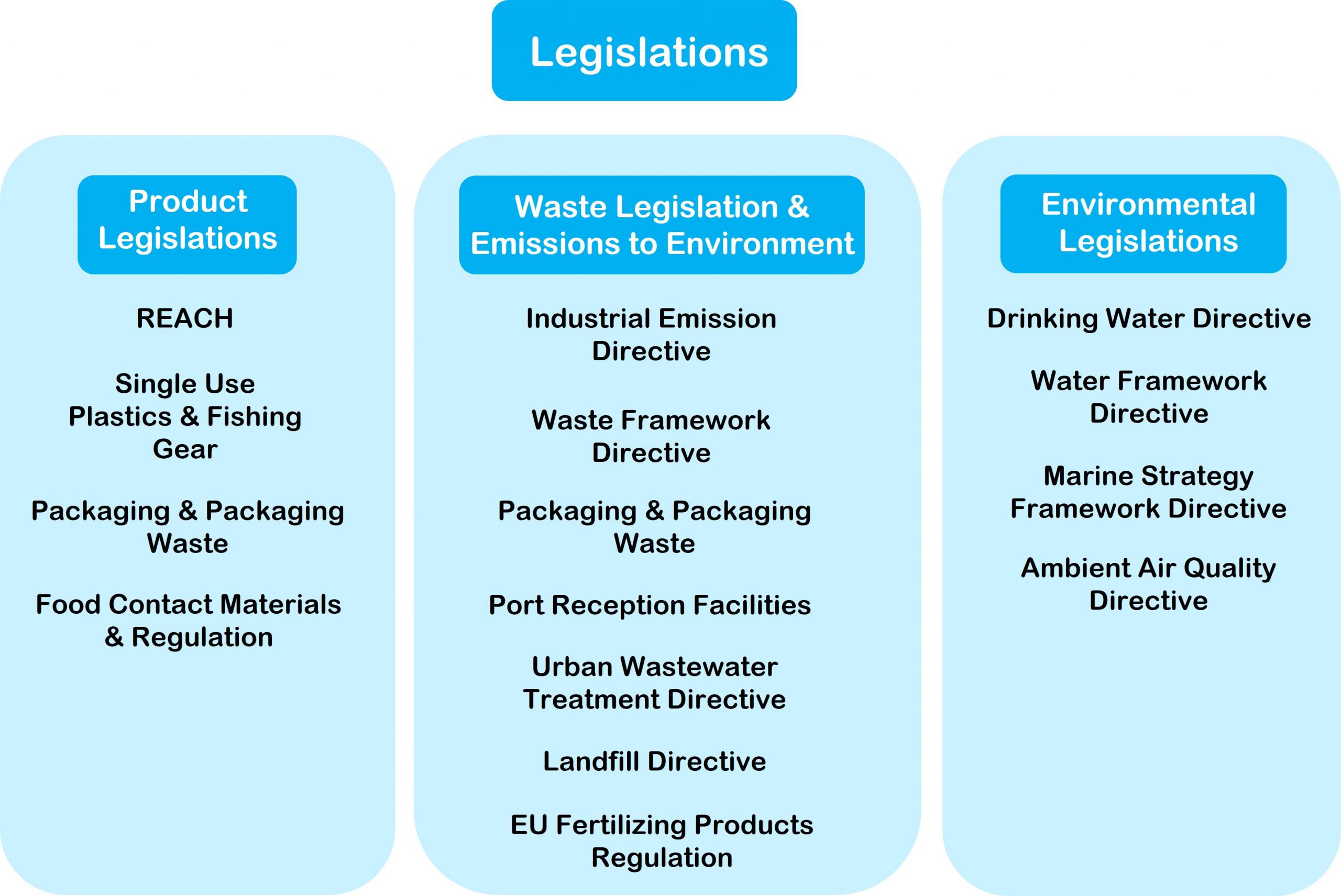

At least in the EU’s Plastic Strategy the issue of microplastics is addressed either directly or indirectly in multiple directives. However, regulations and legislation are not yet on the horizon.

The microplastic restriction proposal was reviewed by ECHA’s committee for risk assessment (RAC) and ECHA’s committee for socio-economic analysis (SEAC) in 2020, and the draft updated accordingly, with a final draft amendment (Annex XVII) released on August 30, 2022. Discussions and a vote on the proposed restrictions will take place between Member State authorities from 2022-2023.

The proposal is certainly a step in the right direction. It acknowledges the serious negative consequences that microplastics can have on both environmental and human health and claims that the restrictions will reduce approximately 500,000 tonnes of microplastics from entering the environment over the next 20 years. Key components in the Annex that should be ensured include:

- Evaluating microplastics under the precautionary principle

- Inclusion of microplastics across all sectors in restrictions, regardless of the polymer type used

- Banning microbeads in cosmetic products with immediate effect (no transition period, as there was a voluntary commitment by the cosmetic industry to remove products with microbeads from the market by 2020)

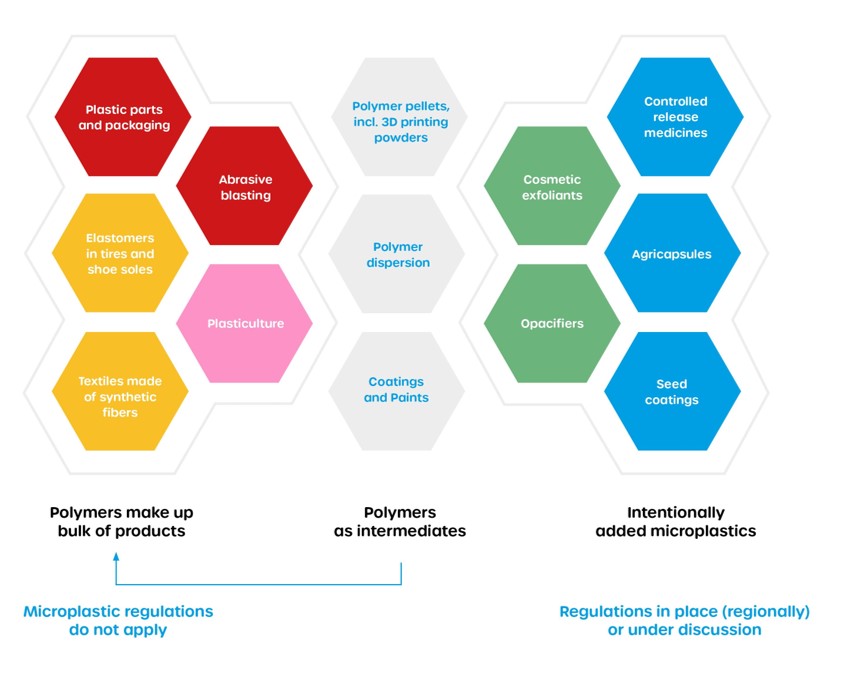

But, there are limitations resulting from ECHA’s proposed definition of microplastics, given as:

Microplastic means a material consisting of solid polymer containing particles, to which additives or other substances may have been added, and where ≥ 1% w/w of particles have (i) all dimensions 1nm ≤ x ≤ 5mm, or (ii), for fibres, a length of 3nm ≤ x ≤ 15mm and length to diameter ratio of >3.

This effectively excludes liquid and soluble polymers and nanoplastics less than 100 nm from the restrictions. According to the Plastic Soup Foundation, this definition applies to only 4% of synthetic polymers used in cosmetics. This leads to the risk that many companies and industries can falsely claim that they are plastic-free, misleading consumers.

Overall, many critical limitations have been identified within the Annex, including:

- Exclusion of carbon-free, soluble (solubility > 2g/l) and liquid polymers from definition of microplastic and associated restrictions

- Including a lower size limit that excludes nanoparticles (<100 nm) from restrictions

- Insufficient testing schemes for “biodegradability” derogation (i.e. not testing biodegradability in all environmental compartments, not testing degradation under realistic environmental conditions, and not ensuring that blends with conventional plastics are prohibited)

- Not including complete ban of infill for sports pitches

- Transition period of 12 years for microplastic ban for make-up, lip and nail “leave-on” cosmetic products

- Reporting measures for plastic pellet loss not sufficient to prevent or significantly minimize plastic pellet losses; transition period should be reduced to 12 months

- Insufficient labeling and instructions for use and disposal

- Derogations for microplastics that lack clear definition of justification, i.e. for: microplastics contained by technical means, microplastics whose physical properties are permanently modified, and microplastics which are permanently incorporated into a solid matrix during end use at industrial sites

Excluding liquid, semi-solid, and water-soluble polymers, along with nanoplastics, from the restrictions will likely lead to an increased market demand and subsequent increase in their environmental concentrations. CodeCheck and The Plastic Soup Foundation further emphasize that the exemption of liquid polymers in restrictions for applications where alternative ingredients already exist, such as for personal care products, is unjustified.

If not now, when?

Due to the long transition periods provided to industries in the REACH proposal, microplastics will continue to be emitted into wastewater streams. Current wastewater treatment plants are not able to completely remove soluble synthetic polymers and solid microplastics. Thus, wastewater effluents emit a considerable amount of microplastics into the environment.

Further, the proposal only restricts intentionally added microplastics – tire abrasion and synthetic textiles, which contribute to over 52% of the primary microplastic load into the environment, are still not being addressed. Further legislation surrounding the detection, monitoring, and removal of microplastics from wastewater effluents should be developed.

We are staying tuned.